Debt Demands & Debunking Distractions for Climate Action

There has been increasing recognition of the climate change-debt trap that many Global South countries face. However, a growing number of proposals have emerged that are inadequate to address the scale of the debt and climate challenges. These proposals risk serving to distract, delay and avoid the deep changes needed to solve the problem. This briefing debunks these false solutions and promotes real, achievable solutions that are based on comprehensive debt cancellation and grant-based climate finance.

Cancel the debt

The problem

From the era of colonialism to the present day, countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean have been forced to rely on borrowing to make ends meet.

Global South countries have been facing increasingly high debts in recent years. External debt payments have increased by 150% between 2011 and 2023, reaching their highest levels in 25 years. Estimates show that 130 Global South countries are

in a critical debt situation.

Many countries have been forced to reduce public spending on essential services like health, education, social protection and climate action to keep up with debt payments. This is fueling a dangerous and harmful cycle of debt and austerity which is further exacerbated by austerity-based conditions attached to IMF and World Bank loans. Not only do austerity-based policies keep countries locked in debt, but they are also causing untold harm to communities across the world, including eroding already weak public care policies and infrastructure, increasing unemployment, and increasing the burden of unpaid and underpaid care work, especially for women and children.

High levels of indebtedness mean that governments lack the resources to invest in the needs of people.

Global South countries are spending 5 times more on debt payments to external creditors than they are on addressing the climate emergency

Furthermore, many Global South countries are turning to their natural resources, including fossil fuels and critical materials, to generate the resources they need to meet external debt payments. This is actively encouraged and enforced by key multilateral lenders, such as the IMF and World Bank. These institutions continue to use their power to promote a colonially rooted, extractive and exploitative neoliberal model of development through their loan-making and projects, despite fierce resistance from indigenous peoples and local communities suffering under debt and austerity.

Demands

Debt cancellation across all creditors for all countries that need it, so that countries are no longer forced to sacrifice basic needs to pay creditors

Debt cancellation should be provided free from austerity conditions so that governments and the public have space to determine where freed-up resources are best allocated.

Resources freed up through debt cancellation must not be counted as climate finance because these resources are not new and additional.

Stop forcing countries to exploit their natural resources, including fossil fuels, to repay debt

Get debt cancellation working now by forcing private lender participation in debt restructuring through legislation in major jurisdictions, including New York and the UK

A major barrier stopping Global South countries from securing adequate debt cancellation is the lack of a robust mechanism to compel private creditors to participate. Private creditors have been allowed to stall, delay, and seek maximum profit in debt negotiations. Nearly all Global South debt contracts with external private creditors are governed under English or New York law. Advocacy efforts for legislative reform are underway in the UK, New York and other jurisdictions.

Promote systemic debt architecture reform by agreeing to a UN debt legal framework

The 2025 Fourth UN Financing for Development Conference poses a unique opportunity for governments around the world to agree to a multilateral legal framework to reform the global debt architecture. A key part of this reform would be the introduction of an independent UN-led debt workout mechanism to serve as a framework for the restructuring and cancellation of illegitimate and unsustainable debts, across all creditors, to a level compatible with sustainable development needs and addressing the climate crisis.

Overhaul the approach to debt sustainability of the IMF and the World Bank and ensure debt sustainability analyses are conducted independently

Current assessments of Global South countries’ debt sustainability are conducted by the IMF and World Bank and are used to stipulate if a country is in crisis and requires debt relief, and if so, how much debt relief they need. The current methodology lacks any democratic consultation, involves a highly subjective and narrow analysis of a country’s capacity to repay and/or take on further debt, and fails to account for the country’s ability to meet the needs of its people, including its ability to address the climate crisis. The IMF and World Bank have recently launched a review of this process, presenting an opportunity for a complete overhaul of how institutions, governments and markets approach debt sustainability.

This is an opportunity to ensure that debt sustainability analyses are done independently and factor in development, human rights and climate crisis concerns.

Dangerous distractions

Debt-for-climate and debt-for-nature swaps

A debt swap is when a government has a part of its external sovereign debt reduced or otherwise restructured in exchange for committing to mobilise the same amount or less for an agreed purpose like sustainable development goals, nature conservation or climate change goals. Debt-for-climate swaps refer to when freed-up funds are invested in climate change adaptation or mitigation, while debt-for-nature swaps refer to when funds are invested in conservation goals.

Debt swaps are not an instrument for overcoming debt crises

Recent cases have shown that debt swaps do not provide substantial or adequate debt reduction and, as such, are not an alternative to debt cancellation. They do not free up sufficient fiscal space for Global South countries to tackle development and climate challenges. One year into the implementation of Ecuador’s Galapagos debt-for-nature swap, there is no evidence of any investments made towards protection, monitoring and surveillance of marine conservation in the Galapagos Islands.

Furthermore, debt swaps can be costly, slow and inefficient, due to the involvement and fees charged by private entities arranging them. If a country is in a debt crisis, it needs rapid and comprehensive debt cancellation to restore its debt sustainability and fiscal capacity to act.

Debt swaps usually lack transparency and can enable creditors to decide what a country’s resources are spent on, overriding community participation and democratic decision-making. In the past, debt-for- nature swaps have triggered human rights violations. They also risk legitimising illegitimate debt, if it is included alongside other debts.

Finally, debt swaps are a distraction from real solutions to the debt crisis. Global North decision-makers are pushing for debt-for-nature swaps and other false solutions to avoid necessary structural reforms. They fail to take due responsibility and accountability for the climate emergency while keeping Global South countries trapped in debt.

Debt cancellation when climate disasters occur

The problem

When a country is hit by a catastrophic external shock like a climate extreme event, there is currently no comprehensive and consistently-applied method of suspending or cancelling debt payments. This means that in many cases, countries continue paying their debts when a climate extreme event strikes, diverting vital resources away from the emergency response and reconstruction.

An external shock like a climate extreme event is also likely to significantly affect a country’s debt sustainability as national- level resources are directed to recovery and restructuring, and because of the necessity of taking on more loans to respond to the disaster, in the absence of adequate grant-based finance for addressing Loss and Damage.

Demands

Automatic debt standstill and cancellation in the wake of a catastrophic external shock

Leaving financial resources available in a country impacted by an extreme event is the easiest, fastest and most reliable way to provide support for emergency relief and the first efforts towards reconstruction.

When a climate-extreme event such as a tropical storm takes place that significantly worsens a country’s economic outlook, there should be an immediate, interest-free suspension of all debt payments from that country across all external creditors. This must go alongside additional, grant-based financing for addressing Loss and Damage.

After a period of assessing the impacts of the shock, a debt sustainability analysis should be conducted, considering the losses and damages and the financing needs for recovery and reconstruction, followed by a debt restructuring, including cancellation if needed, across all creditors.

Dangerous distractions

Climate Resilient Debt Clauses (CRDCs)

CRDCs are clauses that can be added to individual loan contracts to allow countries to temporarily suspend debt payments for an agreed period of time (typically up to two years) in the aftermath of a climate extreme event. Some lenders have proposed starting to include them in loan contracts, such as UK Export Finance, the World Bank, and the African Development Bank.

CRDCs could help suspend debt payments after an extreme climate event and ensure financial resources stay in a country in the aftermath of a shock. However, to be fully effective, they need to be included in all debt contracts across all external creditors (private, multilateral and bilateral) to ensure comparability of treatment across creditors. This is currently not the case. They must also have realistic triggers in place to ensure the clauses are actually implemented when a climate extreme event takes place. Furthermore, debtor countries are likely to have to pay fees to get such clauses added to new loan contracts.

On their own, CRDCs are inadequate to address debt levels in the aftermath of a shock as they only temporarily suspend debt payments, pushing debt payments into the future while interest continues to accrue for the duration of the suspension. This means that when the debt repayments resume, countries may find themselves unable to meet repayments.

CRDCs do nothing about the trillions of external debt Global South countries already have

They therefore do nothing to address the current debt crisis and must not be seen as a solution to the present challenges so many countries are facing.

Grant-based climate finance

The problem

In 2009, Global North governments committed to providing $100 billion in climate finance every year from 2020 until 2025. Not only is this commitment woefully insufficient, but it has not been reached, breaching the trust of the Global South. Conservative estimates suggest that Global South countries will require at least US$5.8 trillion cumulatively to implement adaptation and mitigation commitments by 2030, although the actual needs are likely far higher and will continue to increase as the impacts of the climate crisis mount.

Without adequate climate finance, many Global South countries are forced to find resources for adaptation, mitigation and addressing Loss and Damage elsewhere, including taking on more debt. Loans often come with high interest rates, especially from private lenders, because of the climate vulnerability Global South countries face, creating the opportunity for large profits for creditors if they are repaid in full.

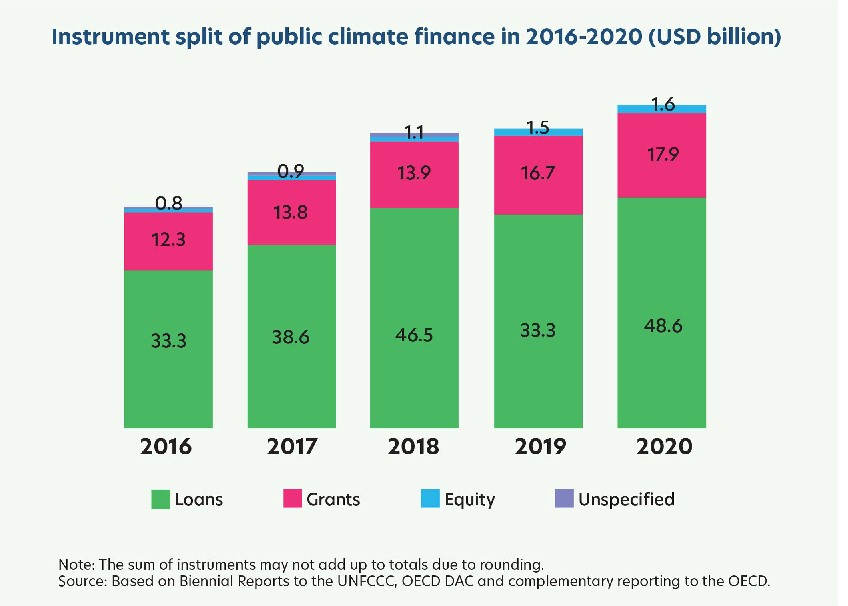

Furthermore, the little climate finance that has been provided largely comes in the form of loans – 71% is provided as loans, with only 26% provided as grants (and 3% as equity). This again adds to debt levels and unjustly forces the costs of the climate crisis onto countries who have done the least to create it.

Demands

Rich countries to pay their climate and ecological debt by providing grant-based climate finance as part of reparations

Rich countries must immediately deliver new and additional, non-debt-creating climate finance, beyond the unfulfilled $100 billion per year, that meets the needs of peoples and communities of the Global South.

To deliver this, a new post-2025 climate finance goal must be agreed at COP29 via the New Collective Quantified Goal process, which delivers grant-based climate finance in line with the needs of Global South countries across mitigation, adaptation and Loss and Damage.

As opposed to “aid”, “compensation” or “assistance”, climate finance must be seen as a part of reparations and an obligation of rich country governments, given their role in creating the climate and ecological crises

(in line with the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities)

The climate and ecological debt owed by the Global North should not only lead to financial reparations, but also to structural reparations, including ecological restoration, phasing out fossil fuel subsidies, ending extractivism, and shifting to decarbonised modes of production, distribution and consumption.

A fully funded and well-functioning Loss and Damage Funds

Agreement must be reached at COP29 for the Loss and Damage Fund to be fully funded with grants and implemented in line with the needs of Global South countries.

As one of the financial mechanisms under the UNFCCC, the Loss and Damage Fund must maintain its independence and democratic governance, and should not be hosted or placed under the auspices of any multilateral bank. It must be transparent and include a robust mechanism for CSO participation that provides adequate space and opportunities for observers proportional to the diverse communities affected by the climate crisis.

Funding under the Loss and Damage Fund must ensure country ownership and direct access, especially to vulnerable groups and affected communities.

Climate finance must:

- Be predictable and urgently delivered by Global North governments through a just and needs-based overarching finance mobilisation target, that meets the needs of Global South countries across mitigation, adaptation and Loss and Damage, reflecting the full costs and equity principles.

- Be grant-based so countries are not pushe d further into debt or forced to pay for a crisis they did not create.

- Come primarily from public sources from Global North governments. It could also be funded by alternative public sources such as green progressive taxation (for example financial transaction tax, wealth tax, or taxes to fossil fuel corporations) or a new allocation of Special Drawing Rights with new criteria for distribution based on need.

- Provided through UNFCCC mechanisms as the most democratic international space available.

- Be new and additional to existing international commitments, including official development assistance (ODA).

- Guarantee accessibility and transparency, and be aligned with human-rights, nature rights, intergenerational equity, and a feminist gender-responsive approach.

- Be seen as a part of reparations and an obligation of rich country governments.

Dangerous distractions

Mobilising private finance for climate action

A key narrative pushed by Global North countries and institutions is that there isn’t enough public money available to provide necessary levels of climate finance (despite huge amounts of money going to sectors that cause harm every year, like the military and fossil fuel subsidies). Instead, there has been a growing emphasis on ‘mobilising’ the private sector to fill this so-called finance gap. However, there is a significant risk that such schemes will exacerbate the debt crisis by adding to debt levels with expensive loans from the private sector.

Some proposals to mobilise private sector finance include:

- Blended finance initiatives that use public money to incentivise or de-risk private sector investments and lending, such as the Just Energy Transition Partnerships. De-risking methods, such as guarantees from Global North governments or institutions, are designed as incentives for investors to lend to Global South countries as a kind of subsidy for the private sector. These guarantees are sometimes presented as a way to reduce borrowing costs, but experience shows that this is not always the case.

- Public-Private-Partnerships, which have a track record of failed projects and public services financialisation and privatisation.

- Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) finance, including the issuance of green, blue or sustainable bonds (or other types of thematic bonds) by Global South governments supposedly to fund projects that have environmental, climate or social benefits. ESG finance lacks adequate regulation, oversight and accountability, and so ‘greenwashing’ is a regular occurrence in the ESG market.

There is a lack of transparency and public accountability, and as a debt instrument, it adds to the debt levels of Global South countries.

The private sector typically prioritises wealth generation and profit, and thus lacks the incentive to fund high-quality, accessible public services and climate action

Subsidising private sector finance has been promoted by rich governments and institutions for many years in the development sector with detrimental outcomes, with evidence that funds often end-up in Global North companies, a lack of transparency, and harmful outcomes for local populations, such as increased user costs and forced displacement.

Increasing the role of Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) in climate finance delivery

MDBs already provide official climate finance – countries in the Global North attributed US$36.9 billion (44%) of their climate finance to multilateral finance institutions in 2020. However, there are calls for multilateral lenders, especially the World Bank and the IMF, to play a greater role in the delivery of climate finance. The World Bank, for example, has a target to increase its financing of climate-related projects from 35% to 45% of total annual financing by 2025.

The calls to scale up multilateral lenders’ role in the delivery of climate finance must be rejected because:

- The IMF and World Bank provide a large part of their financing through loans.

In 2020, 91% of the public climate finance provided by MDBs was in the form of loans, and up to 75% of those loans provided by MDBs were non- concessional (this is, in similar conditions to financial market conditions).

Furthermore, the World Bank’s climate finance reporting is unreliable and non-transparent. - The IMF and World Bank have a long history of attaching austerity-based conditions to loans with harmful economic, human, and environmental outcomes for Global South countries and communities. The World Bank is currently pushing private sector approaches to the green energy transition through its loan-making.

- Many of the activities and programs of the IMF and World Bank are harmful to the climate, such as the financing of fossil fuels, encouraging Global South countries to expand fossil fuel exploitation, or pushing reforms that lead to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions.

- The IMF and World Bank are undemocratic institutions dominated by rich countries that hold the majority of voting rights.

More information

The links between the debt and climate crises

- A Human Rights Based Approach to Debt and Climate Justice ESCR-Net, June 2023

- The Vicious Cycle: Connections Between the Debt Crisis and Climate Crisis ActionAid, April 2023

- The Climate Emergency: What’s debt got to do with it? Eurodad, September 2021

- The debt-fossil fuel trap: Why debt is a barrier to fossil fuel phase-out and what we can do about it Debt Justice, July 2023

- Decoding Debt Injustice: A guide to collecting, analyzing, and presenting data, to shed new light on how the global debt crisis impacts people’s rights Centre for Economic and Social Rights, 2023

Legislative reform to compel private sector participation in debt cancellation

- FAQs on legislative reform to ease debt restructuring for lower income countries Debt Justice, February 2024 (UK law) • Frequently Asked Questions: The New York Taxpayer and International Debt Crises Protection Act Jubilee USA, 2024 (US law)

UN debt workout mechanism

- We can work it out: 10 civil society principles for sovereign debt resolution Eurodad, September 2019

Debt sustainability analysis

- Defaulting on Development and Climate – Debt Sustainability and the Race for the 2030 Agenda and Paris Agreement Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive recovery, April 2024

Debt-for-climate and debt-for- nature swaps

- Debt Swaps Climate Action Network, May 2023 • Miracle or mirage? Are debt swaps really a silver bullet?

Eurodad, November 2023 • Initial assessment of Galapagos debt-for- nature swap a look from civil society after one year of operations Latindadd, May 2024

Climate resilient debt clauses

- Before the (next) storm. Debt Relief as a response to Natural Disasters in the Caribbean Jürgen Kaiser for Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung, April 2019 • Global Sovereign Debt Monitor 2024 Erlassjahr, April 2024, pages 37-40 • Riders on the storm – How debt and climate change are threatening the future of small island developing states Eurodad, October 2022

New Collective Quantified Goal

- Economic justice civil society’s joint submission to the UNFCCC consultation for the Seventh Technical Expert Dialogue on the New Collective Quantified Goal on climate finance Civil society join submission, August 2023