Reflections on IMF/World Bank Annual Meetings 2024

80 Years of Bretton Woods Institutions

A Need to Reform the Global Financial Architecture for Social Justice:

A Feminist Economic Lens from the Global South

Introduction

Eighty years after the creation of the Bretton Woods institutions, the Global South faces a deepening debt crisis, exacerbated by a myriad of challenges—COVID-19 pandemic fallout, climate shocks, rising borrowing costs, colonial violence in Palestine and Lebanon, and the ongoing genocide of Palestinians in Gaza by the Israeli occupation. Today, over half of the world’s low-income countries are either already in debt distress or at high risk of it. In the MENA region, countries such as Lebanon, Tunisia, and Egypt allocate significant portions of their national budgets to debt servicing. Lebanon alone, currently under aggression, spent 50% of its national budget on debt repayment in 2023, while Tunisia and Egypt struggle with surging debt-to-GDP ratios, exceeding 90%.

While the IMF provides emergency financing to distressed nations, its loans often come with harsh austerity measures that prioritize debt repayment over local social needs. This results in significant public service cuts, disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable populations, particularly women. Essential sectors like healthcare, education, and social protections are underfunded, leaving women doubly burdened—both by a lack of access to public services and the absence of gender-responsive social protection programs.

Adding to the burden are IMF surcharges—penalties imposed on countries exceeding their borrowing limits. These surcharges have intensified the challenges for nations like Argentina and MENA countries, including Tunisia, Egypt, and Jordan. Such policies expose the contradictions within the IMF’s mission: while it aims to support economic stability, it often enforces conditions that deepen poverty and inequality.

On October 11th the IMF Executive Board reviewed surcharges and approved reforms, reducing surcharges by 36%, a move that came after a lot of advocacy around the issue by civil society including MENAFem. These reforms were highlighted as a “win” during the meetings, but remain half-measures to an unfair system that punishes countries for being indebted and adds to their debt burdens instead of helping them.

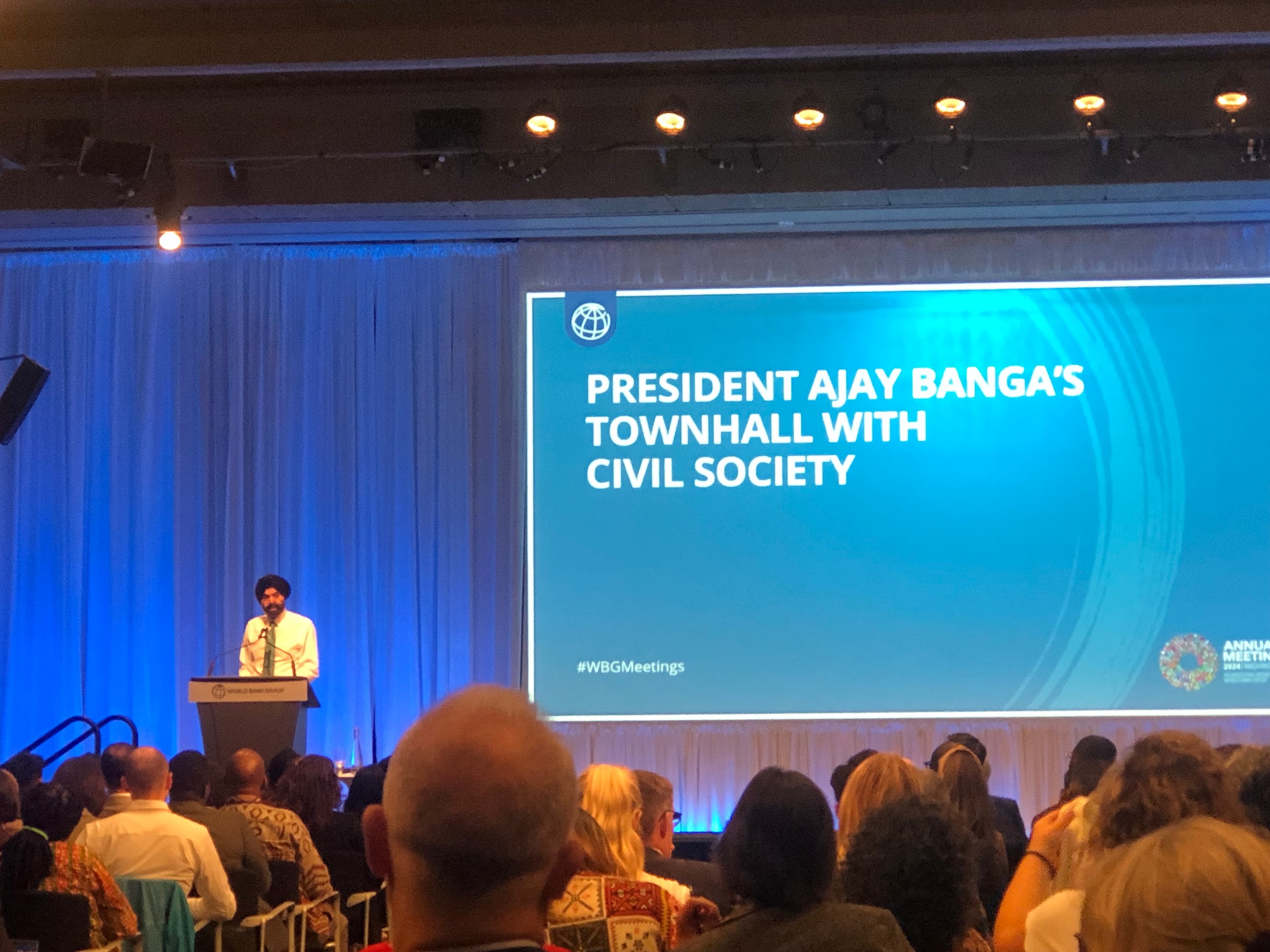

Some of the competing moments for ‘highlight’ of the week included: hearing “high debt low growth,” the IMF’s seemingly new slogan, 3 different times–the first being in the Townhall with Georgeva; Ajay Banga’s “poverty is a state of mind, not just a state of being”; the number of times IMF staff refuted ever imposing policies on countries–and the insistence that all our problems come from our governments; and hearing IMF staff double down on a statement saying “there will be harm” (to women).

Governance

Current quota calculations weigh GDP at 50%, favoring larger economies, while criteria that prioritize human development make up only 5.5% of voting power. This unequal distribution results in stark disparities: for example, Sub-Saharan African nations, which are home to numerous borrowing countries, control only two seats on the IMF’s executive board, with the announcement of the addition of a third during the IMF Civil Society Town Hall. As a result, developing countries often have little influence over the policies that directly affect them, particularly in times of financial crises.

Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), introduced by the IMF as an international reserve asset, have become a vital instrument for countries in crisis. SDRs provide liquidity without increasing debt or imposing policy conditions, allowing countries to stabilize their currencies, finance imports, and repay IMF obligations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF issued $650 billion in SDRs, the largest allocation in history. Many developing countries effectively used these resources to procure vaccines, support social spending, and repay debts, mitigating some of the pandemic’s economic fallout.

However, disparities persist due to the link between SDR allocations and IMF quotas, which favor wealthier nations. Decoupling SDR allocations from quotas is essential to ensuring a fair distribution of resources. Expanding SDRs in the future could support countries in debt distress and address broader global challenges, such as climate change.

Gender

The new World Bank (WB) Corporate Scorecard, introduced as a strategic management tool, consolidates over 150 indicators into 22 cross-cutting metrics aimed at streamlining performance measurement. However, from a feminist economic perspective, the scorecard’s approach to financial inclusion raises significant concerns. While the scorecard tracks gender outcomes through two specific indicators—measuring the percentage of women benefiting from economic opportunities and accessing financial services—it remains inadequate for addressing the deep-seated structural barriers faced by women, particularly in the Global South.

The focus on short-term outcomes risks neglecting the underlying causes of gender inequality, including the unpaid care burden, precarious employment, and restricted access to credit that disproportionately affect women. Additionally, the financial inclusion model embedded in the scorecard has been criticized for driving indebtedness without addressing these root causes, further marginalizing women economically. As feminists from the MENA region, we advocate for a more transformative, rights-based approach that integrates gender across all policy dimensions, ensuring that progress towards sustainable development aligns with social and economic justice goals. Without such integration, the new scorecard risks perpetuating the disparities it seeks to measure and undermining meaningful advances in gender equality.

The IMF is still intent on seeing women only as vehicles for economic growth, which was seen in the presentation of a gender toolkit that was devoid of any measurement of the impact of their own policies on women in the Global South. When asked about why, we heard back that the toolkit had to help them sell gender equality to country teams. When faced with questions on austerity, various iterations of “the money has to come from somewhere”, “high debt and low growth”, and “blame your governments” were uttered. IMF staff in the Civil Society Policy Forum (CSPF) asserted that “there will be harm” to women in response to questions on the “do no harm” policy and that they just try to reduce it as much as possible.

CSPF sessions witnessed IMF staff refute ever imposing policies on countries and could have been more informative had the representatives actually engaged with real responses, but it seemed like they were all reading from the same script. Some representatives were more open than others, but it remained painfully obvious with most that they had a pre-approved set of talking points.

Outside the formal sessions, far more invigorating, authentic, collective, and disruptive gatherings were taking place. Civil society organizations, feminist and climate activists, and academics from across the world were able to come together during the meetings to collectively strategize, take action, and experience collective feminist joy. From strategy meetings to our Resist & Revive feminist party, politics of care and solidarity were practiced. Despite the absence of any real official mention of the ongoing genocide of Palestinians in Gaza apart from a few infuriating comments (ie. Banga’s comment saying the Bank created a committee made from Israelis, Palestinians, and other Arab nationalities to help Palestinians), the calls for a free Palestine dominated the civil society space.

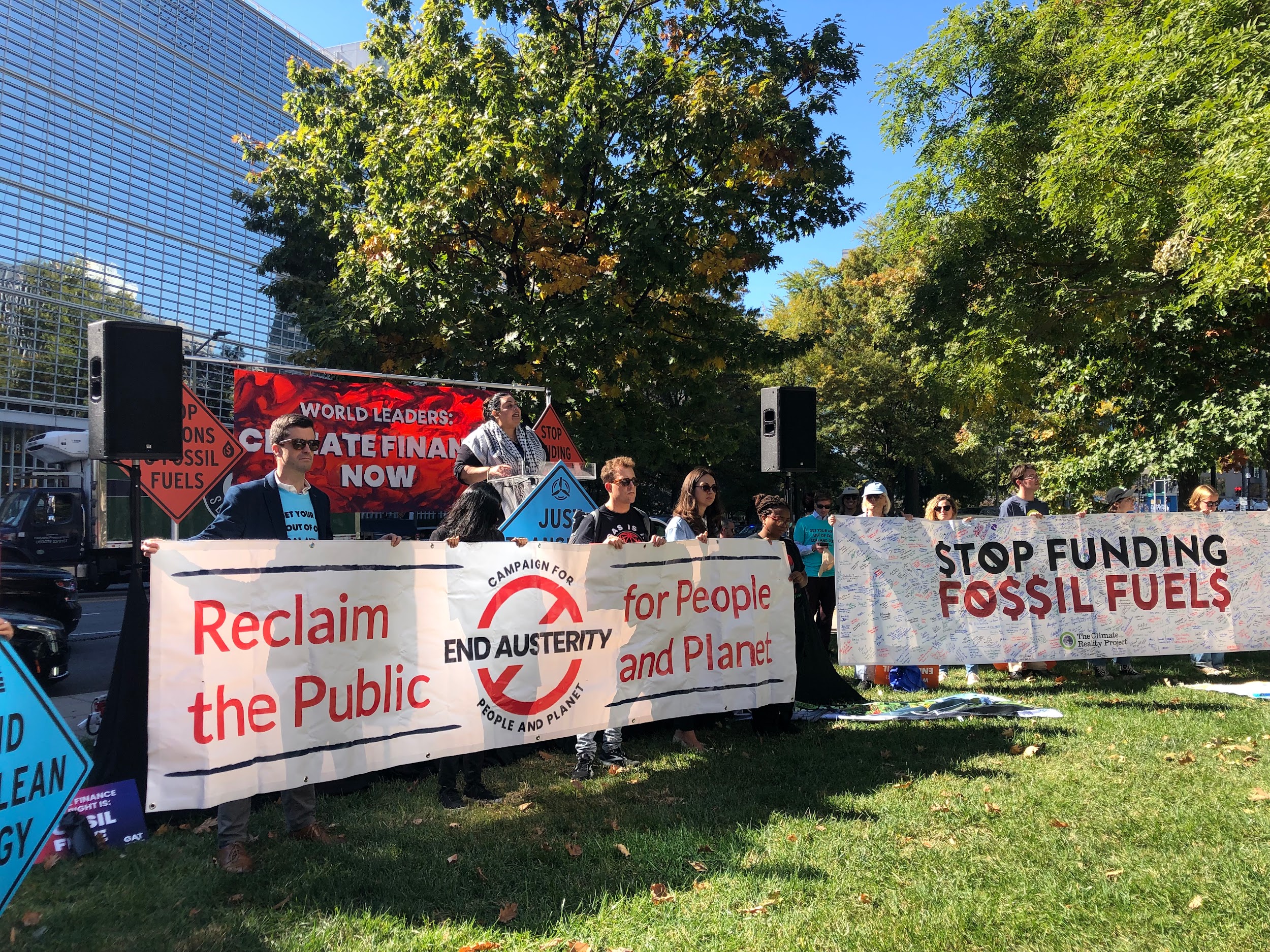

CSOs held a protest and marched from the World Bank to the White House to demand an end to financing fossil fuels, an end to austerity, and adequate climate finance, amongst others. These different dynamics prompt the question: how can civil society globally build a collective movement that transcends these performative gatherings and mounts a real challenge to structural inequality? This discussion was amplified through the different CSO strategy meetings and during multiple discussions with CSO partners on gender, racial, socioeconomic, and ecological justice

Climate and Fossil Fuel

The urgency of the climate change challenge has reached a critical tipping point, with scientists warning that immediate and drastic action is needed to avert catastrophic consequences, yet during the annual meetings of 2024, civil society has repeatedly been asked to “be patient”. Despite the overwhelming evidence and calls for decisive measures in various fora and from various voices in the Global South, many governments in the Global North constituting the major shareholders of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund remain dismissive and prioritize short-term economic interests over long-term just transition and climate resilience.

We’ve seen the International Development Association (IDA) and Executive Directors congratulating themselves for very limited and insufficient progress on the IDA replenishment and the decision of the review of surcharges despite civil society’s calls for further progress. Managing Director of the WB Ajay Banga was questioned about the continual the funding of gas projects in the World Bank Town Hall, and instead of giving clear responses on timeline or plans for divestment and frameworks for just transition, Banga simply responded that renewable energy is not economically competitive.

Similarly, while discussing IFC’s obligations to prevent its activities from contributing to climate change harms, the IMF representative asserted that clean energy was simply still too costly. This favouring of the neoliberal revenue-focused model manifested itself in the consistent affirmation that the only possible way to mobilize enough resources for a just transition is through the private sector. Despite civil society’s effort to highlight recommendations by the International Energy Association (IEA) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to stop funding new fossil fuel projects if we want to maintain the 1.5 degree goal.

Additionally, civil society members took on multiple opportunities to refer to the ramifications of fossil fuel projects on vulnerable communities, especially on women, to which the responses reverted to denying responsibility. This denial of responsibility came in the form of either shifting blame to local government or blame lack of information about the harm caused by projects funded through IFIs, despite being in a room full of people trying to explain the harm caused by these projects.

Time moves at different speeds. There’s the speed through which time moves when you are discussing the policies you’ll enact in different countries, and the speed through which time moves when policies are being enacted in your countries. The former is slow and kind, devoid of urgency and accountability, and the latter is fast and cruel, devoid of rhyme or reason, filled with urgency and undeserved punishment. The suits in the offices in which the time moves slow must join the field where time moves fast and mistakes cost lives.

Call for Structural Reform of the International Financial Architecture

As expected, discussions yielded underwhelming outcomes on governance reform, debt and austerity, or fossil fuels—confirming once more that the IMF and World Bank’s power structures serve the elite and privileged, far removed from the genuine needs of the Global South. This systemic imbalance sidelines the voices and realities of the Global South while continuing a narrative of “fiscal consolidation,” cloaked in rhetoric such as “the money has to come from somewhere” meant to deflect its true identity: austerity. In reframing these policies as prudent measures, the IMF and World Bank perpetuate the cycle of economic tightening, stripping social welfare systems and crushing local economies under the guise of “reform.”

The upcoming 2025 Financing for Development (FfD) conference offers a critical opportunity for civil society and developing countries to advocate for a fairer international financial architecture. Amidst ongoing discussions on global financial architecture reform, civil society is anticipating the upcoming FFD4. The Civil Society FFD Mechanism aims to achieve a UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation to address tax havens, tax abuse by multinational corporations and other illicit financial flows. One of its goals is to agree on a UN Framework Convention on Sovereign Debt that would comprehensively address unsustainable and illegitimate debt, including through extensive debt cancellation. The CSO Mechanism advocates for the establishment of an international public credit rating agency at the UN and for achieving a UN Convention on International Development Cooperation, including establishing a mechanism for the fulfilment of ‘aid debt’ owed to the Global South for decades. Some of the other CSO goals are to have systemic risks posed by unregulated or inadequately regulated financial sector instruments and actors assessed and to establish a UN intergovernmental global technology assessment mechanism.

The civil society mechanism’s vision involves: establishing a UN intergovernmental process to review and transform international financial institutions and Multilateral Development Banks, overhauling the international financial architecture; establishing a UN intergovernmental process to conduct a thorough review of the sustainable development outcomes, human rights and fiscal impact of public-private partnerships (PPPs) and other private financing instruments; achieving a UN multilateral agreement for a coordinated and permanent termination of Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanisms that has empowered transnational corporations to sue governments in confidential tribunals on a range of issues including debt, tax and climate action. An effective FFD would need to ensure fiscal space and scale up international cooperation for decent jobs creation and universal social protection in line with SDGs and ILO standards and to ensure human rights and gender equality as a cross-cutting lens.

At the meetings, mentions of global financial reform were in between “the UN is expecting too much from us, this is not achievable” and “the IMF is leading in global financial reform”. Civil society’s calls for radical, systemic change echoed through the week, forming a counter-narrative to the well-guarded status quo inside the official sessions. This was a moment to reimagine our collective future, resisting the multilateral inertia and envisioning economic models rooted in gender, racial, socioeconomic, and ecological justice.