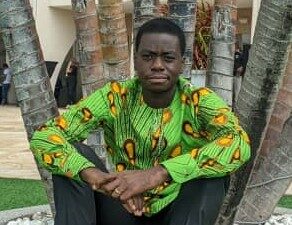

Edem Yaovi Dadzie,

Sociologist, journalist, and administrator of the information website https://lepapyrus.tg/, a pan-Africanist media site

This year, 2024, it will be 80 years since the establishment of the so-called Bretton Woods institutions. The Bretton Woods agreements, signed in 1944 and ratified in 1945, established a new international monetary system that would promote inter-state cooperation and international trade. Indeed, 10 years after the economic crisis and depression of 1929, the Second World War broke out with the failure of the League of Nations. A solution had to be found. But what? And in whose favour? Did we really want to find an effective system of international cooperation on a basis of equality, or did we simply want to find a way of subjecting the rest of the planet to a well-defined domination?

After so many years, the objective conclusion that can be drawn is that the countries of the South are the survivors of the international financial system. It is more than obvious that these institutions serve the victorious powers of the Second World War rather than the development of the countries lagging behind. You only have to ask yourself how many years it took these powers to recover from the Second World War, and to be at the level they are today, to understand that these so-called aids are real poisoned gifts. Unfortunately, some countries, particularly in Africa, swear by the Bretton Woods institutions instead of focusing on endogenous solutions.

The successive crises affecting the countries of South Asia, then Russia and the countries of Latin America, have contributed to a profound questioning of the policies pursued by these institutions, whose legitimacy has been greatly weakened as a result. Fortunately for Russia and the countries of Asia, they quickly realised the need not to depend entirely, and addictively, on the international financial institutions.

Today, these countries have achieved spectacular industrialisation by making their own economies more competitive, relying more on domestic financing and diversifying their partnerships. Who can dispute the fact that Russia, China, Japan, South Korea, North Korea etc. have become serious competitors to the Western countries that control the Bretton Woods institutions, even threatening to overtake them?

In Latin America, we are not there yet, but it is just a matter of time, since these countries have also understood the deception and are in the process of assuming their responsibilities. The countries of the global South know that unless they free themselves from the sterile domination of the Western powers, including the United States, they will never emerge from underdevelopment. The Brics initiative to create a development bank could rebalance the international financial system, which is highly unfavourable to the weakest and most vulnerable.

The old criticisms are still with us and deserve to be amplified

One of the criticisms levelled at the Bretton Woods institutions is the lack of democracy in the way they operate, particularly the voting system based on the economic weight of each member state. Many observers strongly question the predominant influence of the United States and the consequent lack of influence of the countries of the South. Bernard Cassen, President of the Attac association, deplored the fact that “the weight of the South, despite being the first to be affected, is virtually non-existent in the IMF, because of the American lock-in: each country counts not for one, but for the number of dollars in its quotas” (2000).

We must not lose sight of the fact that it is above all the G7 that plays a dominant role within the international financial institutions, as Jean-Michel Séverino, former World Bank Vice-President for Asia, has pointed out. Leaders, particularly in Africa, are therefore often obliged to accept conditions and policies that do not suit their people, at the risk of not having access to funding for their development projects. This is the ugly face of international relations, a thinly veiled dictatorship.

Transparency is also lacking within the Bretton Woods institutions. The image of “discreet, even secretive” institutions, to use the terms used by Friends of the Earth with regard to the IMF, persists. The lack of transparency in the IMF’s accounts means that member states do not have a clear picture of the institution’s financial situation. The IMF is the only organisation in the world whose accounting records contain no information on the extent of its assets and liabilities.

The Bretton Woods institutions are pushing the countries of the South into the abyss

Echoing the criticism of the abusive role played by the United States within the Bretton Woods institutions, the monolithic vision of development conveyed by these institutions has been strongly criticised. This criticism relates first and foremost to the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), which for a long time favoured privatisation, the opening up of markets, the restoration of macroeconomic equilibrium at all costs, and so on.

Many non-governmental organisations believe that these measures have not led to real economic development, but rather to the deprivation of natural resources and the breakdown of state structures, leading to the destructuring of internal trade. In the 1970s, developing countries took on more and more debt because borrowing conditions were apparently favourable.

The World Bank, private banks and the governments of the most industrialised countries encouraged them to do so. From the end of 1979, the rise in interest rates imposed by the US Treasury as part of the neo-liberal shift and the fall in commodity prices radically changed the situation. The flows reversed and, during the 1980s, creditors made juicy profits on the debt.

Since the financial crisis in South-East Asia and Korea in 1997, net debt transfers to creditors (including the World Bank) have risen sharply, while at the same time debt has continued to climb to unprecedented heights.

As early as 1960, the World Bank identified the danger of a debt crisis in the form of the inability of the main indebted countries to support the growing repayments. The warning signs multiplied throughout the 1960s until the oil crisis of 1973. The heads of the World Bank, private bankers, the Pearson Commission and the US General Accounting Office (GAO) all published reports highlighting the risks of the crisis.

With the rise in oil prices in 1973 and the massive recycling of petrodollars by the major private banks in industrialised countries, the tone changed radically. The World Bank no longer spoke of a crisis. Yet the pace of indebtedness was accelerating. The World Bank entered into competition with private banks to grant as many loans as possible as quickly as possible.

Until the crisis erupted in 1982, the World Bank used a two-pronged approach, telling the public and indebted countries that there was nothing to worry about and that any problems that arose would be short-lived. This is the line taken in official public documents. The second line is taken behind closed doors during internal discussions.

An internal memorandum stated that if the banks perceived that the risks were increasing, they would reduce lending and “we could see a large number of countries find themselves in extremely difficult situations” (29 October 1979). This is how the crisis was precipitated. We should not forget the poor governance that was under way in several countries, particularly in Africa.

And when countries found themselves over-indebted with non-viable (white elephant) or non-existent projects, SAPs were the only way to further impoverish the population. According to the neo-liberal logic embodied by the international financial institutions, the state must stop implementing social policies and spending and step aside in favour of the private sector, which is considered to be more efficient.

It must limit itself to repression (police, justice) and defence. Public companies in African countries are being sold off at knock-down prices in order to free up cash as quickly as possible for debt repayment. The privatisation of the public companies that used to provide basic services (water, sanitation, telecommunications, electricity, education, health care) has had the direct consequence of making these services scarcer and more expensive, and making them much less accessible to poor people living in rural areas, the majority of whom are women.

To compensate for the public provision of basic services, many women and girls are forced to increase their invisible, unpaid work. From now on, it is they and not the state who will unofficially provide these services for the rest of the community.

Debt followed by structural adjustment is not gender-neutral

Contrary to the message conveyed by neo-liberal orthodoxy, it has to be said that debt and the macroeconomic measures associated with it are in no way gender-neutral. On the contrary, debt is a colossal obstacle to gender equality on a global scale. The SAPs, imposed by the World Bank and the IMF on indebted countries in the South to ensure repayment of their external debt, not only deepen women’s poverty but also harden and deepen gender inequalities.

The SAPs, renamed “Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers” (PRSPs) in the 1990s, undermine any process of emancipation for women. In addition, the debt and the policies it imposes reinforce patriarchy, a thousand-year-old system of oppression and domination of women, which establishes a sexual division of labour assigning men to the “productive” sector (production of goods and services with a market value and therefore a source of income) and assigning women to the so-called “reproductive” sector. This confines them to the role of educators and producers of human capital. They are thus responsible for ensuring the social reproduction of human societies. It is now easier to understand why any genuine process of emancipation for women involves fighting against debt, an essential component of neoliberalism, which, together with patriarchy, enslaves women wherever they live on this planet and prevents them from enjoying their most fundamental rights.

The situation of women in the South has continued to deteriorate as a result of the deregulation of the labour market, which has reinforced their exploitation. This has resulted in the homogenisation of informal, precarious, flexible and undervalued work, and a race to the bottom in both wages and labour rights. In 2009, 71% of women in paid employment in Black Africa were in precarious jobs, compared with no less than 8 out of 10 in South Asia.

The increase in cash crops for export demanded by the SAPs required more labour to grow them and more space for production. In addition to their work on food crops and in the “reproductive” field, women had to work in their husbands’ fields, which increased their workload. Gradually, export crops replaced food crops, which were forced to retreat to marginal land. Women were forced to cultivate more remote and less fertile land. Their production suffered as a result.

This reduction in food production, combined with the decline in women’s purchasing power, threatens the food security of women farmers and their families, and increases malnutrition, especially among children and girls. Studies have shown that the nutritional status of women and children is poorer among cash crop farmers, especially those who grow tobacco, coffee and cotton.

Women do 75% of the farming in Africa and produce 70% of the food. But for legal reasons, they cannot buy, sell or inherit land. Men get the land, women the work. Financial institutions reinforce discrimination in access to credit. Women are granted less than 1/10th of the credit allocated to small farmers on the African continent.

This very limited access to credit, means of production and land is a further obstacle to women’s agricultural and textile production. In addition, thanks to the liberalisation of markets, foreign products, which are generally subsidised and often come from the agri-food or light industry sectors, can now reach local African markets without hindrance and sell at much lower prices than those charged locally.

Women in these countries, often confined to small informal production units, were unable to resist the growing competition from these imported products. Little by little, women’s activities and jobs disappeared. So the liberalisation of world trade is much more synonymous with the loss of income for women in the South and the destruction of the local economy than with economic growth, as the rhetoric of the international financial institutions would have us believe. Essayist Bertrand de Jouvenel observes: “Just as the political mechanism of the United Nations proved wholly inadequate to the real post-war situation, so too did the economic mechanism set up at Bretton Woods”.

Edem Yaovi Dadzie

Sociologist, Journalist, Administrator of the information website https://lepapyrus.tg/ , the pan-Africanist media

Bibliography

Tavernier, Yves. “Critiquer les institutions financières internationales”, L’Économie politique, vol. no 10, no. 2, 2001, pp. 18-43.

Series: 1944-2024, 80 ans d’intervention de la Banque mondiale et du FMI, ça suffit! Around the founding of the Bretton Woods institutions, by Eric Toussaint, Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debts (CADTM)