Impact of Bretton Woods institutions on women’s access to health care

Karim Tarek,

Introduction

Defenders of human and development rights face a great challenge, especially when working on issues that are closely linked to their societies. While believing that defending rights is an arduous long journey, questions remain on why human beings struggle to enjoy their basic rights, including women’s access to health services.

Human development indicators offer basic tools in measuring social justice. Health status outcomes, such as maternal and maternal mortality rates, infant and child mortality rates, and life expectancy are the most human development indicators, besides access to drinking water and others, which put health at the heart of metrics used to measure the state of development and social justice.

The relationship between health and human development is also an organic relationship in its positive and negative aspects. The improvement of the health indicators of citizens and their freedom from diseases is a basic measure to improve their productivity, quality of lifestyle and standard of living.

Despite Egypt’s long history with various health care systems, it was not possible to raise the state’s obligation to provide universal health services to all citizens until after 2014, when the constitution enshrined that in Article 18 which stipulates the right of all citizens to access health services by obliging the state to establish a comprehensive insurance system, as well as preserve health resources and make sure they are fairly distributed at the territorial level, while allocating at least 3% of government spending to the health sector.

There is no doubt that this important step was the starting point to make health services accessible to all, as a mandatory human right rather than a service or charity, especially after the government’s launch of a modern insurance system open to all Egyptians. This was achieved following a law on universal health insurance drafted after consultations with the civil society and health experts. Afterwards, multiple presidential initiatives were launched including the Women’s Health Initiative in 2019, which aimed at the early detection of breast cancer and noncommunicable diseases (diabetes, hypertension, obesity), providing health education to Egyptian women and improving the general health of women in Egypt by providing free examinations and raising awareness of the importance of regular health care.

At the same time, international reports and local data on coverage rates and the conditions of health services in Egypt showed a lack of access to health insurance services, especially amongst women, where only 8% of those eligible were benefiting from health insurance service. Approximately 86% of the poorest groups in Egypt did not know they were eligible to health insurance in the first place, despite although the health law covered 60% of all Egyptians.

Egypt is among the countries that spend the least on health care in the Middle East and North Africa, with an individual out-of-pocket spending at about 61%, due to systemic deficiencies and inequalities in health finance. Although more than 95% of the population live within 5 kilometers of health facilities, these health centers are often not equipped to meet the actual needs of residents. Meanwhile, reports highlight a shortage of medicine and the lack in clear guidelines for chronic diseases and limited number of specialists, which leads to reduced health benefits.

The Corona virus has also significantly affected the provision of health services in the countries of the region due to the decline in tax revenues, increased debt repayment, increased spending, and prioritizing pandemic-related treatments. The pandemic also affected the rates of inequality between rural and urban areas. This context worsened the access and the quality of women’s health services, while exacerbating the conditions of poor families, pushing women- who provide for 30% of Egyptian households- to abandon their health care needs so that their children could receive health care.

The debt crisis and its impact on the health budget

Human rights researchers are interested in whether services benefit those who deserve them, focusing their efforts on documenting the violations they may arise while trying to access basic services. As far as health services are concerned, obstacles facing women’s access can easily be monitored and documented. These hurdles are often due to a lack of resources or a failure to properly implement laws as well as the implementation of unpropitious policies or verbal instructions. Assessments and opinion polls can also be conducted in some contexts, despite challenges faced while seeking information, especially in restricted contexts. This represents a major obstacle in human rights research.

As a researcher who is not specialized in economics, I could, however, monitor the link between women’s access to health care and Egypt’s monetary policies, which is characterized by heavy debt, mainly since 2016. A clear inverse relationship between reliance on loans and the decline in access to health services and social protection was found. In the next paragraphs, I try to offer an analysis of austerity crises and spending rates on health and link this to the inadequate health services offered to women.

Egypt began an era of dependence on foreign debt since 2016 until now for the purposes of improving social protection programs and economic reforms. These loans have had a deep negative impact on social justice and the distribution of services due to the austerity policies the government to service debt, including additional expenses. This had direct consequences on the health sector, whose budget this year was limited to 1.2% of GDP, in violation of the constitutional provision stipulating 3% as a minimum percentage.

The following table shows Egypt’s total loans and reasons for obtaining them since 2016 from the IMF and the World Bank in particular

| Institution | Loan Amount (Billion USD) | Date | Purpose |

| International Monetary Fund (IMF) | 12 | 2016 | Extended Credit Facility Program – Economic Reform Program |

| 5.2 | 2020 | Rapid Financing Instrument – COVID-19 Response | |

| 3 | 2022 | Extended Credit Facility Program – Economic Reform Program | |

| World Bank | 3 | 2015 – 2019 | Development Policy Financing – Economic and Social Reforms |

| 2.8 | 2020 | Special Drawing Rights – COVID-19 Response | |

| 0.5 | 2022 | Supporting social protection programs | |

| 0.5 | 2022 | Supporting food security and infrastructure |

The table is prepared by the researcher by using the data announced by the State Information Service entitled Egypt and the International Monetary Fund and other news sites

While these loans aimed to strengthen social protection programs, develop the Egyptian health system- including through a World Bank funding of $530 in 2018 to combat hepatitis – support the universal health insurance system and expand the scope of family planning services, the high cost paid by the government to meet loan expenses over the past years came to the detriment of social justice, social protection and inequality, leading to exacerbating poverty rates and reducing access to basic services.

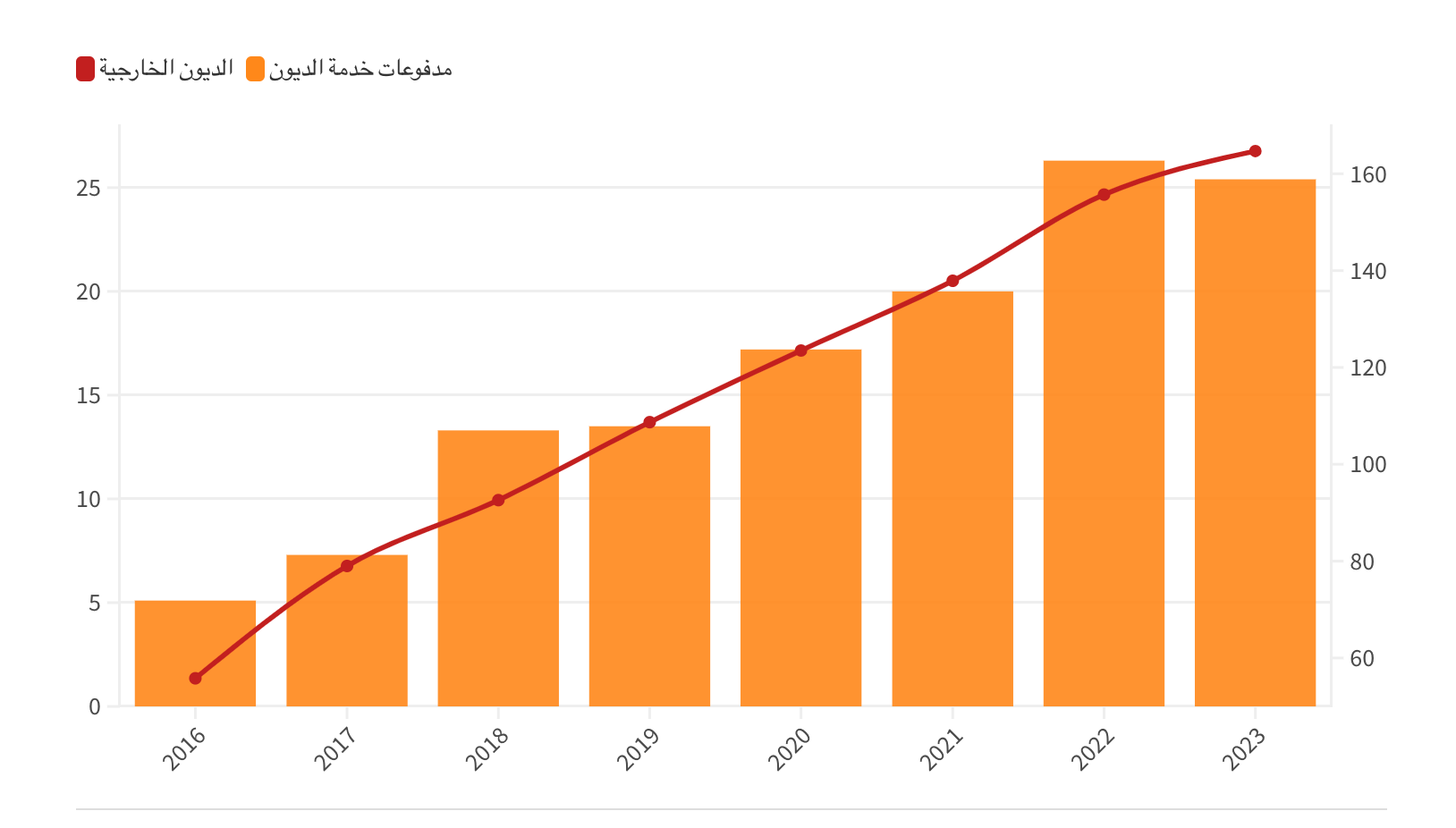

Red arrow represents foreign debt and orange stands for debt service payments

Source: Telegraph Egypt article titled “Debt interest payments eat up state revenues. Causes and Solutions”

The growth in interest payments was mainly caused by higher interest rates together with soaring inflation, in addition to the decision to liberalize the exchange rate last March.

The consequence of increased debt servicing was manifested in a drop in spending on education from 4% of GDP in 2014 to 1.9% in 2024, while spending on health shrunk from 1.4% in 2014 to 1.2% in 2024.

High interest rates on debt made the state take many austerity measures such as the gradually cutting in subsidies, increasing the prices of public health services, reducing energy loads and other policies that directly impact the daily lives of citizens.

-

How debt expenditures have affected women’s access to health care

The state approved in 2012 the Health Insurance Law for female breadwinners, which includes divorced women, widows and female-headed families. This was based on a social register by the Ministry of Social Solidarity. The law provided for financial contributions tin line with the social status of women. While the rest of the women, whether employees or pensioners, were entitled to the health coverage specified for them, such as health insurance for pensions and health insurance for female employees.

Despite the low levels of public health care services, as mentioned before, this law was a landmark legislative step. It theoretically provides sustainable health care services such as medicines for chronic diseases and costly operations in a way that tries to preserve the social and economic status of families, but awareness of this coverage was below expectations, especially since most of the beneficiaries among women breadwinners are from the poorest social classes. This reflected a lack of access as well as insufficient awareness.

However, with the worsening of the Egyptian economic crisis in recent years, many female breadwinners were surprised by the cancellation of their subscriptions from the health insurance system. This was monitored by civil society organizations and reported by the media. The government and parliamentarians were in the denial, even though the employees responsible for this reported that there were verbal instructions not to include women breadwinners and to transfer them instead to other treatment initiatives for the poor.

Difficulties were not only limited to accessing health services. Personal experiences and on the ground observations reflected procedural difficulties linked to accessing health services. In March 2024, the health ministry has liberalized the prices of some services offered by public hospitals. These included healthcare services offered to women, such as family planning, pregnancy follow-ups. Higher prices led many women to abandon seeking medical care, resorting instead to local associations or risking no medical examination.

In 2019, the state launched the Women’s Health Initiative with the aim of detecting chronic diseases, breast cancer and raising awareness about public health. The initiative was funded by the government and some international organizations. It achieved great success in spreading awareness, especially about breast cancer, teaching women self-examination and referring them to the hospitals for their treatment. But at the level of chronic diseases, women were referred to the same public hospitals and health insurance facilities, which were already reeling under the aforementioned crises, such as the lack of medicine and slow procedures.

In 2020, the maternal and fetal health care initiative was launched as part of the 100 million healthy initiatives. It includes:

- Medical examinations for the early detection of B virus, HIV, and syphilis.

- Follow up the condition of the mother and newborn for 42 days after birth to detect risk factors.

- Counseling for the prevention of diseases and dispensing the necessary micronutrients to the mother during pregnancy and puerperium.

- Establishing an integrated database and linking it to health facilities to facilitate follow-up of the mother’s condition and provide the necessary treatment.

Despite all these stated goals, the women are surprised that the sonar service, for example, is not covered and priced at amounts beyond their affordability.

As for the level of universal health insurance and despite some success in providing healthcare for women and in terms of infrastructure in hospitals, there are still remaining dysfunctions associated with the renewal of subscriptions and the determination of contribution rates, which may hinder access to health services.

-

Comment

In this paragraph, we can derive the impact of debt directly and indirectly on women’s access to health services as follows:

- The decrease in the percentage of health in GDP, which is set by the constitution at 3%, amid high debt ratio and an increase in debt interest. This directly affects the equipping of hospitals and health units in a way that falls short of meeting the needs of women.

- The liberalization of the exchange rate directly affects the import of medical materials and resources necessary in the pharmaceutical industry, leading higher medicine prices in local pharmacies.

- Raising the prices of services provided by public health facilities and dispensing only one medicine on the ticket led to an increasing reluctance and discontent among women, who shun seeking health services from hospitals, especially those relating to family planning.

- The high cost of living and the economic crisis have pushed women to seek additional revenue and pay little attention to their own health issues, focusing instead on their children’s access to public health services, because they are unable to cover the costs for themselves and the children.

While the state tends to market the idea of presidential initiatives as a form of supporting social protection for female citizens, in the end they remain vertical initiatives that lack a mandatory character and legal legitimacy.

Recommendations and conclusion

We will not dig deep into alternatives for debt, given the existence of recommendations by economists in this regards. Instead, we will offer in the next paragraphs recommendations and proposals relating to enhancing women’s full access to healthcare, a responsibility that should be upheld by the state and civil society in tandem.

- Empowering and informing women about access to sustainable health coverage platforms and promoting awareness of the constitutional right to health and how to deal with violations that may occur while accessing services. This can be achieved in cooperation with local NGOs and by using social media;

- Work on manufacturing medicines locally to overcome the crisis of drug shortage and achieve self-sufficiency.;

- Invest in improving hospital infrastructure and repairing medical devices and facilities at the local and central levels to give women full and equal access to health services;

- Directing support and funding to civil society organizations that adopt the idea of raising awareness on basic rights and building the human rights monitoring capacities;

- Strengthen communication mechanisms targeting women to monitor and evaluate access to services and take the necessary advocacy campaigns to provide health umbrellas for all;

- Opening the public sphere and disclosing necessary information to conduct studies aimed at achieving a comprehensive reform of the health sector;

- Provide independent oversight mechanisms for public services and strengthen accountability and governance.

To conclude, we believe that reforming the health system requires in the first place an ambitious political will and a belief in the right to health as a constitutional obligation, in addition to giving priority to investing in women’s health, with the participation of all stakeholders and experts, including the patients themselves and civil society organizations, while implementing economic and social recommendations.